August 7-9, 2009

Shortly after his 11th birthday, I took my son Liam on a two-day, 90 mile bike trip between Duvall and Cle Elum, over Snoqualmie Pass and through the 2.3-mile Snoqualmie Tunnel. The next summer, when I was 47 (!), we climbed Mt. Adams together. Both trips required significant training … last year we did a lot of bike riding around town plus a few longer trips, such as from our home in North Seattle to the Red Hook Brewery in Woodinville, with the rest of our family joining us at Log Boom park in Kenmore. This year we did training hikes of Mt. Constitution on Orcas Island (my 9-year-old son Jay joined us), Mt. Si, Summerland on Mt. Rainier, and Rampart Lakes.

The training hikes were at least as much for my benefit as Liam’s — my legs were killing me after the Mt. Si hike. I was OK on the uphill, but the downhill laid a hurt that kept me from biking to work for several days.

I’d climbed Mt. Adams twice before, to its summit when I was 30, and to Piker’s Peak three years ago.

Liam took a bus from downtown Seattle to Tukwila, where I picked him up shortly after noon on a Friday, then we drove to Portland, east to Hood River, and north to the Trout Lake ranger station where we procured our Volcano Pass. We stopped along the way in Centralia for lunch at Burgerville, a restaurant chain Liam remembered fondly from previous trips through Oregon. We arrived at the trailhead at 6:30 PM, and were on the trail 20 minutes later.

Unfortunately, this only left us about 90 minutes before sunset and I didn’t want to set up our tent in the dark, so we climbed about 1000 feet in the trail’s first three miles to the Morrison Creek headwaters and set up our tent in a campsite just a few feet from the trail. I didn’t count on more hikers coming up after us, as it was 8:15 PM and the sun was nearly down. It was a beautiful spot.

True to form, a pair of women came up while we were setting up our tent. We boiled water for dinner, which was a pouch of Lipton Noodles and Sauce. Like almost everything I’ve ever prepared in the wild, it was good, but to Liam it was astonishing: “This is great!” he said. I told him everything tastes better in the wild. After dinner we lay down side by side on a campsite in a nearby meadow and watched the stars come out. We were at 6500′ and I’d been hoping we would get a sky full of stars to the horizon, the Milky Way, and some shooting stars. Well, we saw more stars than we do in the flatlands, but the sky near the horizon was hazy, and even looking straight up it wasn’t clear enough to see the Milky Way, though we did see a few shooting stars and one satellite.

When I was younger I remember lying in a similar position, even at a lower altitude in a Los Angeles suburb, and being absolutely conscious of the inexorable wheeling of the stars. This night wasn’t clear enough for that, but it was still nice to lie next to my son and point out many of the northern constellations, seeing many more stars than we normally do.

We finally went into the tent at 11:00 PM. I woke at 1:00 AM when a group of hikers went by, and again at 4:00 AM when two more groups walked past, then again at 5:00 AM, their boots crunching in the trail’s rocky sand, their headlamps briefly lighting up the inside of our tent like daylight. OK, lesson learned: don’t camp so close to the trail; climbers hike at all hours.

Next morning, I dragged myself to the creek to boil water for instant oatmeal. The only flavor we had enough of for both of us was the “original” flavor, ie unflavored, which for instant oatmeal amounts to the flavor of shredded paper. I walked back to the tent to let Liam know that breakfast would be ready in five minutes. To my surprise, he got up, dressed, and walked down to the creek in less time than that. And no, not even the added flavor bonus of the wilderness was enough to make that “original flavor” instant oatmeal palatable. I separated the dried cranberries from a bag of gorp and added them to the oatmeal to see if that would help, and it did indeed, but it still wasn’t what one might call delicious. We were down to three liters of water so I boiled up two more from the creek. I also moved the tent much farther from the trail.

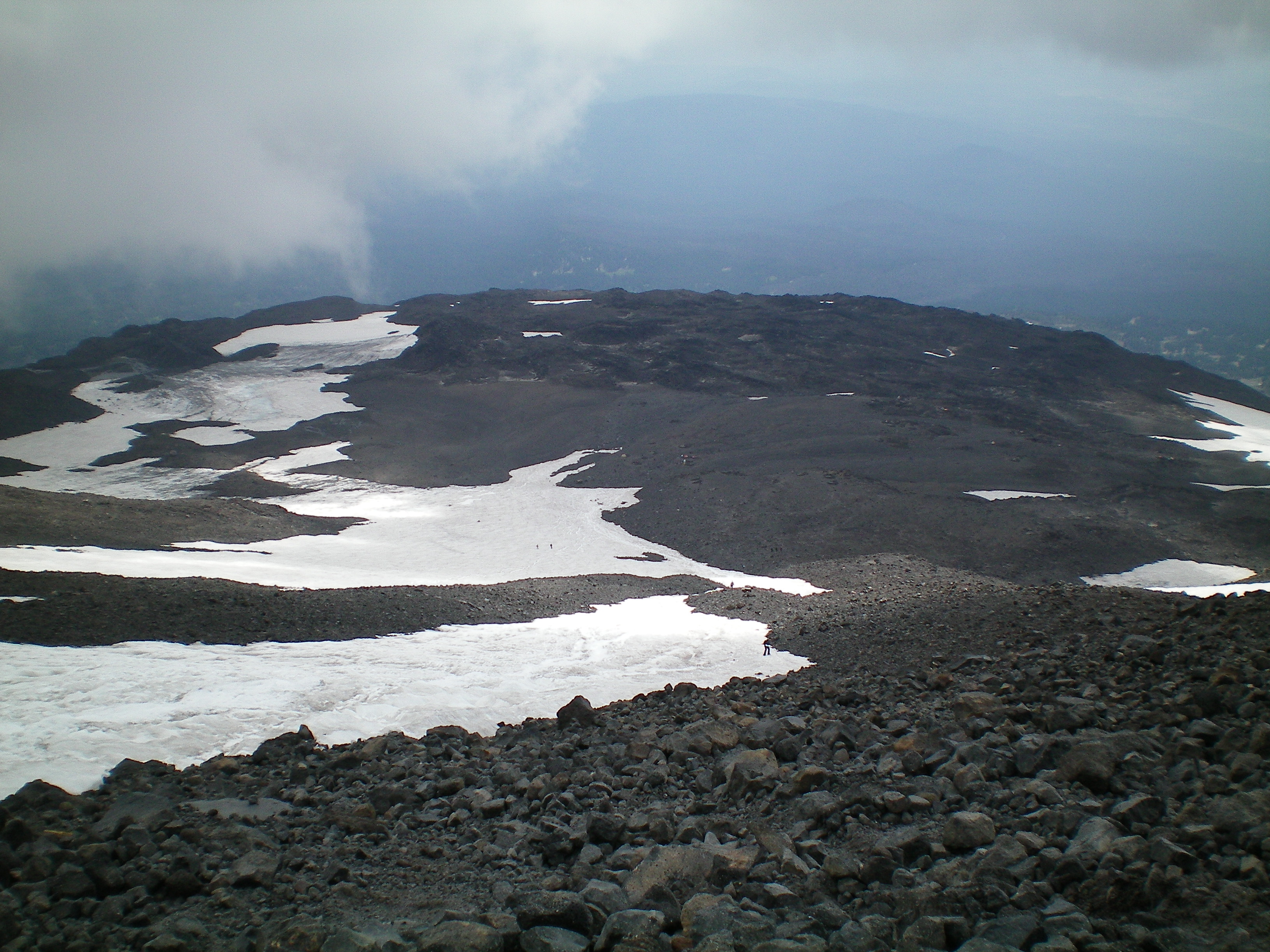

We started at about 9:00 AM, leaving our tent and sleeping bags and pads, taking breaks every hundred feet of altitude until the trail ended where it met the Crescent Glacier at 8000′. Liam got his first taste of hiking on snow/ice as we climbed the remaining 1400′ to The Lunch Counter, itself at the foot of an 1800′ pitch to the Pikers Peak false summit. We had lunch in the shade of a big rock. Then we climbed 200′ to the base of the really steep part, whereupon Liam realized that he’d left his sunglasses at our lunch site. He left his pack (my daypack) with me. Before he returned, the weather changed. I’d already seen a cap cloud form and grow on Mt. St. Helens, which I explained to Liam usually means that moister air was arriving, and sure enough before his return a series of amorphous grey clouds were playing peekaboo between us and Pikers Peak. We started climbing anyway.

We didn’t have crampons or ice axes. I’d climbed to at least the level of Piker’s Peak twice before without using them, and while I knew they were recommended, I hadn’t wanted to fool with them this time. But as we climbed past the 10,000′ level, the snow we were climbing, already steep, was getting icy. And the last thing I wanted to do on a slope as steep as this was to lose traction as the snow turned to ice. People coming down past us were reporting that conditions higher up had turned cold, windy, and icy. I told Liam we might have to turn back.

“Are you joking?!” he said, incredulous. A few sunbreaks followed. “See, it’s clearing up!” But the clouds returned each time. We’d climbed roughly 1/3 of the way to Piker’s Peak, reaching the top of a lobe of scree not far below what looked like a brief pause in the slope’s steep part. But each step at this level was one we had to cautiously chop into icy snow. I crossed the glissade trench to the top of the scree lobe and put on my long thermal pants, briefly mooning a few people as they glissaded past from higher up. Liam put on the waterproof pants I’d made sure to ask that he pack. It was cold, windy, and icy, and we were still far from the false summit. Liam got into the trench and started down. I did, too, but quickly realized that my external-frame pack wasn’t a good choice for action like this: its two vertical supports stuck down to the level of my butt while I slid down. They were useful as brakes, but as heavy as I was on an icy slope with slippery shorts over my thermal pants I was barely able to control my descent. Then the stitching on my 20-year-old pack gave way and the pack separated from its hip belt. I’d slid maybe 100′ down, mostly out of control, and now my butt and hands were numb and my pack was busted. Liam was out of sight below, but he’d been whooping and hollering at how much fun he was having before he got too distant to see. I walked the rest of the way down, chopping my heels into the snow before every step to make secure footholds. Going down was surer and a lot quicker than it had been going up. Liam awaited me at the bottom of the steep part.

Behind us, the weather at the false summit had cleared. “Aw man!” Liam said. He told me he’d figured out how to brake by leaning back and letting his pack drag. Later he told me that glissading had been more fun than he’d ever had on any amusement park ride. I can see why: I don’t know of any amusement park rides that are 700′ high and where you control your own descent. We boot-skiied down the glacier back to 8000′, which was fun for both of us. Before long the summit clouded up again and Liam conceded that we’d made the right choice by descending. The rest of the descent to our campsite was uneventful, though I enjoyed showing Liam the Crescent Glacier’s terminal moraine, a huge pile of gravel partially intruding into the valley where we camped.

Back at the camp, the creek had dried up during the day, so we were going to be short on water. Liam lay down in his sleeping bag and said how nice it was to lie down. I did the same, and it was indeed, but Liam needed to go. We’d brought along a human waste bag from the Ranger Station, so I asked him to cross the creek and do his business there. I would clean up after both of us. I woke 15 minutes later when Liam said he was done. I headed over and tried to do mine. I heard a clatter of stones and looked across the ravine to see a marmot crossing a field of slate to sit on a big overlooking rock. We looked at each other for some time. Eventually I zipped up and packed our leavings into the provided bags. A couple had made their way into a campsite maybe 30 yards away from our latrine site and were engaged in quiet conversation, unaware of both me and the marmot. I’d heard them from farther away but didn’t know they’d come closer. I smiled and waved, letting them know about the marmot. They barely acknowledged me. I called out to Liam to bring his camera and our binocs, then we watched the marmot and enjoyed the view; we looked south towards the Columbia River gorge and across to Mt Hood, with several lines of not-insignificant ridges between, a light haze in between making for a beautiful vista.

Back at the campsite, I boiled two cups of water and we had ramen. Liam was blown away by how good it tasted, and asked that we have ramen the next morning rather than instant oatmeal, even a more palatable flavor than “original”. I asked if Liam wanted to hike out today, as there wasn’t much left to do until the stars came out, but he said he wanted to stay another night because he didn’t want our trip to end, which warmed my heart. We only had 2 1/2 cups of water left, but that was easily rectified in the morning.